The Mago Way: Rediscovering Mago, the Great Goddess from East Asia (Review)

When I began my own Goddess studies, I devoured the “Great Goddess,” “Gods and Goddesses of the World,” and “World Mythology” compilations that were available and noticed the complete absence of information about Korean goddesses. In some ways this is reflective of the nature of these anthologies, which attempt to move beyond Euro-centrism while avoiding the production of a huge, unwieldy, and costly volume. Paradoxically, this world overview approach creates or reinforces a chauvinism of its own. What becomes distilled for comparative study reflects the amount of material available. In the 1980s there didn’t seem to be anything in English for a casual reader about Korean goddesses. I can’t say that with authority, because finding Korean goddesses wasn’t exactly a mission of mine; only an absence that registered without my thinking too deeply about it. Helen Hye-Sook Hwang’s The Mago Way: Rediscovering Mago, the Great Goddess from East Asia, is a welcome and much-needed addition to Goddess studies that begins to fill this void.

Although The Mago Way mentions Korean goddesses, it is not about goddesses per se but about a Korean way of conceptualizing the Great Goddess. Except this conceptualization is not just Korean, but an understanding of Goddess cosmology that crosses national, ethnic, and geographic borders, using an ancient Korean manuscript as a foundational text. This manuscript, The Budoji, is an origin story believed to have been written in the 5th century.

The Budoji tells of the self-creation of the Great Goddess, called Mago, as a primordial sound emanating from a wave of light. Mago gives birth parthenogenically to daughters, two of them, who in turn each give birth to four daughters. Mago’s eight granddaughters create music attuned with Mago and move the “eight planets” in harmony with Mago’s vibration. The granddaughters are proto-humans, establishing four races. They in turn give birth to male and female humans, establishing the sexes.

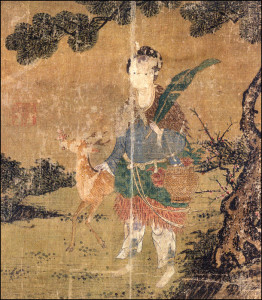

Hwang traces Mago through folktales, other goddesses, and place names throughout East Asia. She describes how Taoism, Buddhism, and Confusionism are derivative of the ancient Mago Goddess religion, shedding more light on these philosophies. She finds parallels with Magoism in the Greek Muses and Hindu Matrikas. She says “Mago’s affinity to other Goddesses becomes ever evident when we examine how the triad and parthenogenesis, the two paramount themes of the Magoist Myth, are in ancient gynocentric cultures and religions around the world.” Hwang demonstrates a strong background in radical feminist thealogy and shows how Mago fits within this framework.

The Mago Way is fairly short and readable, with illustrations. It is introductory, rather than comprehensive, and Hwang promises to go into the mythology in more depth in future volumes. I am not in any way qualified to assess Hwang’s scholarship; still, I sense this is an important book. I would not consider this volume esoteric or specialized in any way, but a valuable addition to overall Goddess studies.